The first time I saw a priest take off his clerical collar was in a car park before we boarded a train to Boston. Fr Al explained that it was too dangerous to be identified as a Catholic priest on public transport – he knew priests who had been bashed up on that same train line – and he placed the collar in his briefcase with a sigh. I was unsettled, not just because of the threat to his safety but because it seemed improper, like the removal of a sheriff’s badge or an army officer of his epaulettes. Without this insignia, Fr Al looked more like a Mafia don than my university chaplain. It felt wrong.

Witnessing someone else take away a priest’s clerical collar, however, is profoundly more disturbing.

On Monday, the Feast of the Annunciation, the monks of Notre Dame Priory in Tasmania held their second clothing ceremony. There was only one novice monk to be clothed, but in contrast to the previous novices Fr Mark Withoos arrived in the black cassock and biretta of a priest…

…and his guests included a dignified cohort of clergymen.

Father Prior recognised this distinctive and unusual circumstance in his exhortation to Fr Mark, noting that thus far he had “appeared to the world in black”, testifying to his “desire to die to the ways of the world”, and that St Benedict “warns the abbot not to readily receive a priest into the community”. He explained that “the priesthood holds with it the greater burden of responsibility for giving examples of humility, obedience and strict discipline”.

Not unsurprisingly, Fr Mark seemed somewhat tense after this solemn exhortation. However, when he was given the name Brother Augustine Mary, his features relaxed into an expression of peaceful joy.

I cannot overemphasise what a privilege it is to witness this moment. Apart from the Father Prior and one or two monks, I am the only one who can see the face of the novice monk as he receives his new name. And no photograph can capture the physical proximity and actual experience of being just a few feet away. As one of the monks’ mothers commented to me today, “you can feel it even when you can’t see their face.”

[By the way, this is one of the reasons I am so grieved when guests insist on taking photos on their mobile ‘phones when there is a professional photographer present – quality aside, they miss out on the actual experience and make their own life vicarious by experiencing it through a lens.]

I photographed Notre Dame Priory’s first clothing ceremony, so I should have been prepared for what came next. But there is good reason that these ceremonies have traditionally been private affairs. The stripping of a priest of his cassock and collar feels almost sacrilegious to the onlooker. Though rather fanciful on my part, I could not help thinking of the English martyrs being disrobed for execution. Monastic camaraderie notwithstanding, the gravity of what was taking place was palpable.

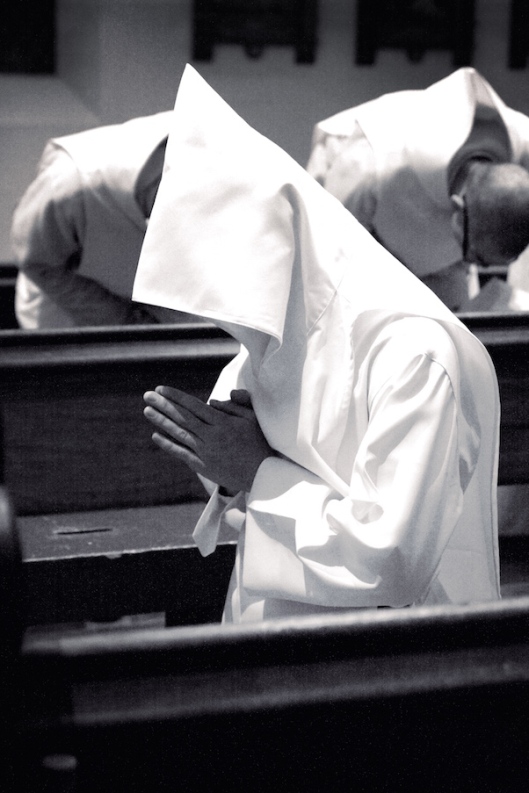

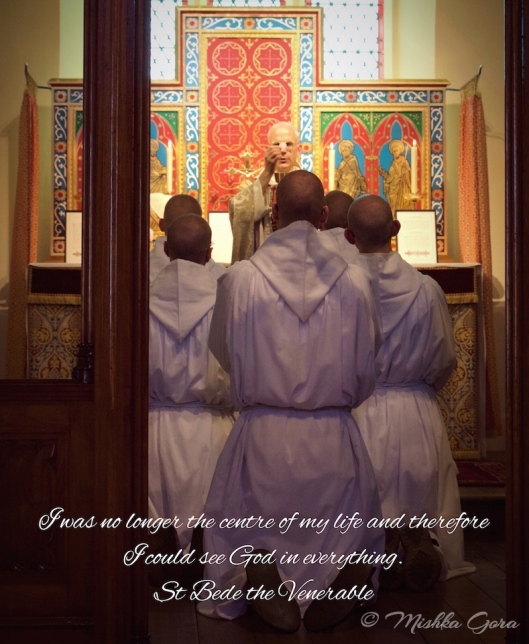

This sombre stripping of a past life swiftly shifts, though… into the adoption of the “sweet light” of Our Lady and her mantle. This is perhaps, I’m guessing, the reason it is not called a reception or initiation ceremony but a clothing ceremony. For, in the sense that they are representative of what lies within, clothes do indeed maketh the man. “If black symbolises death, white symbolises the new life of holiness.” The prior, Dom Pius, replaced the priestly robes of which Br Augustine had been stripped with the bright and pure habit of the Benedictine monk: “Today, you will don the shining white of Our Lady’s habit, placing yourself in a very special way under her Immaculate mantle.”

The sun dipped behind the horizon as Br Augustine Mary completed his transfiguration, and the birds in the rafters continued their own song of praise. The priest’s cassock, surplice, and biretta lay abandoned on the altar as an offering to Our Lady of Colebrook.

Nightfall usually brings calm, a lull in activity and a settling down to rest, but on this occasion the cool Midlands dusk heralded restrained ebullience and many expressions of joy. I congratulated Br Augustine on his “demotion” and he voiced his wonder that he could be so blessed as to have a second vocation.

I do not claim to understand the calling to monastic life. It is, I suspect, slightly beyond my ken. There are, however, glimpses available to us, perhaps when we are on retreat, holding vigil, or in the company of these monks whom we cherish. What strikes me every time I am with them is the immensity of their choice, not just to enter the religious life but to daily live the life of ora et labora.

Over and over again, in all things great and small, they choose what we in the secular world tend to avoid. They embrace the contemplative life while we rush on thoughtlessly; they embrace the toil of labour with all its meniality and repetitiveness. They are not forever “trying to find time” in order to leave some mark on the world. It is as if they understand that man’s “greatest desire, the desire for permanence and immortality, cannot be fulfilled by his doings, but only when he realises that the beautiful and eternal cannot be made”. *

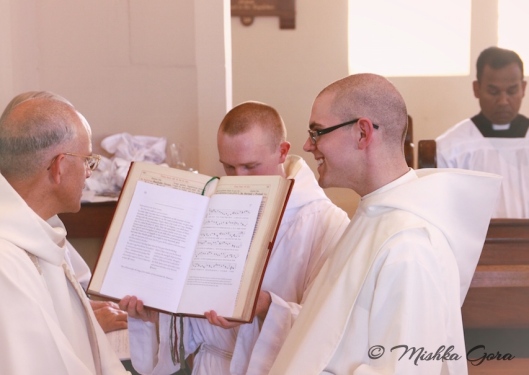

My favourite moment of the evening, the point at which my throat caught and my photographer’s instinct raised the camera and took the shot, was in the quiet of the church afterwards. One brother knelt before another, unthinking yet thoughtful, without hesitation yet deliberate in service. Both smiled contentedly as they looked upon the shoes of a life Br Augustine Mary had just forsaken.

“The human condition is such that pain and effort are not just symptoms which can removed without changing life itself; they are rather the modes in which life itself… makes itself felt. For mortals, the ‘easy life of the gods’ would be a lifeless life.” *

Click here to view an album of photos from the ceremony.

* Quotes from Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition.

You must be logged in to post a comment.